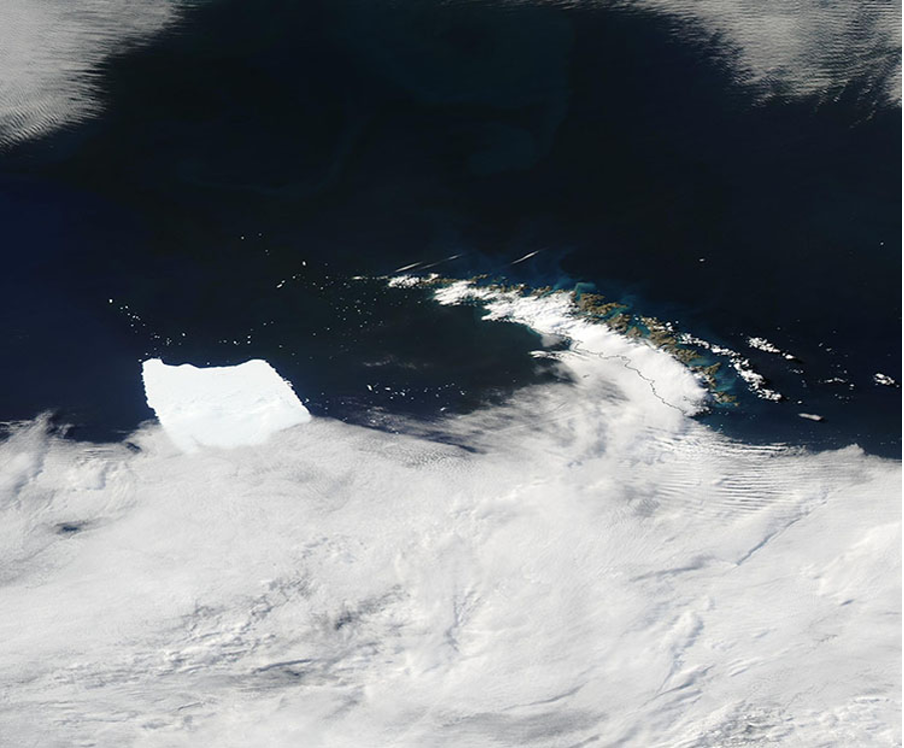

Image credit: A23a (on the left) stuck on the seabed off the coast of South Georgia Island (on the right), 6 March 2025. Image by MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC.

In 1986, Antarctica gave birth to A23a, the world’s largest iceberg. Drifting away from the South Pole, the once 3,900 sq km giant – twice the size of Greater London, according to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) – lodged itself in the Weddell Sea for over 30 years. In 2020, A23a broke free.

Resuming its course north in the South Atlantic Ocean, A23a recently approached South Georgia Island, alarming the world. South Georgia “is an incredibly rich ecosystem, covered with animals and birds”, explains Ted Scambos, senior research scientist at the University of Colorado. The initial thought was that A23a would collide with South Georgia, threatening and disrupting local wildlife.

However, beginning of March 2025, the iceberg ran aground on the seabed, 70 km off the coast of South Georgia. Now, “the general consensus is the [ice]berg is far enough offshore that is unlikely to be a major hazard to the shore-based flora and fauna”, announces Christopher Shuman, recently retired glaciologist from the University of Maryland.

Image credit: Map data ©2025 Google. Marker and label added by Zoe Duc.

A23a poses other risks, with its immediate impact threatening local marine ecosystems.

Currently stranded on the seabed, the iceberg, still weighing millions of tonnes, is eroding rocks and crushing all benthic organisms, such as corals and anemones. As Scambos describes, “It’s not fun for benthic organisms … because it’s total destruction”.

Yet, this catastrophe will be short-lived, as these ecosystems are used to icebergs in the region. Scambos wants to reassure, “[Benthic organisms] will be eradicated, but the surrounding areas will quickly fill in and regenerate after the iceberg is melted off or drifted off by currents”.

As for penguins, the risk is likely no longer present. A23a is stationary and should slowly melt away from South Georgia. Shuman clarifies that the melted freshwater from the iceberg, which could potentially freeze at the surface of the ocean and block feeding grounds for penguins, is now too far north to freeze.

Image credit: A23a seen on 7 January 2024, north of Antarctic Peninsula. Photo by Jean Wimmerlin on Unsplash.

Although the size of A23a is rare, “This has happened many times before”, explains Scambos. Icebergs are part of a natural cycle in Antarctica, according to BAS, that also brings unexpected benefits. Scambos adds, “On balance, if the iceberg is out in the southern ocean, it’s probably in general a positive thing”.

When melting, the ice unlocks the nutrients trapped during freezing and releases them in the ocean, proliferating life around A23a. “Some of the icebergs have a high dust concentration… [which] is a valuable source of iron for the ocean ecosystem”, says Scambos. Indeed, most oceans are deprived of iron.

As it melts, iron released in the ocean supports the marine food chain. As explained in a Stanford Report’s article, iron stimulates phytoplankton growth, and “phytoplankton are the foundation of the marine food chain”, according to NSIDC. Phytoplankton feeds the smallest specimens, like krill, which then feed penguins, which in turn feed larger animals, such as orcas or leopard seals.

An increase in phytoplankton helps to create a more productive ecosystem by supporting the food chain. This productivity enhances the ocean’s ability to absorb and store carbon. Indeed, according to an article published in March 2025 by Science, “Phytoplankton absorb about as much carbon from the atmosphere as all land plants.”

A more productive marine ecosystem will, therefore, retain more carbon “from the surface ocean,” explains Dr Meijers in a BAS statement, helping to reduce ocean and atmospheric temperatures.

Shuman insists, “It’s an area of further investigation”, and scientists still need to learn more from A23a’s impact.

Although A23a is not directly linked to climate change and seemingly provides considerable benefits, global warming’s impact on Antarctica remains a focus. Dr Meijers outlines via BAS, “The ice shelves have lost around 6000 giga (billion) tonnes of their mass since the year 2000… attributed to anthropogenic climate change”.

As temperatures increase daily, we should expect a greater ice mass loss in Antarctica, increasing the number of icebergs. While some icebergs, like A23a, may temporarily be beneficial, the consequences are more complex. The increasing number of icebergs, linked to global warming, could contribute to irreversible seafloor destruction, habitat loss, and disrupt delicate marine ecosystems.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment