Image credit: Kiribati. Photo by Vladimir Lysenko (I.), licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

“We have this deep connection with the ocean because… it has been our main source of livelihood for thousands of years”, introduces Robert Karoro, an I-Kiribati and national coordinator for a local NGO, Kiribati Climate Action Network (KiriCAN). Now, climate change and “the rising sea levels have turned our ocean against us. It no longer provides for us, it threatens us”, adds Miriam Moriati, a young I-Kiribati, president of the Kiribati Rotaract Youth Club, and members of local NGOs.

Kiribati is a country located in the centre of the Pacific Ocean, composed of one island and 32 atolls. Most of Kiribati’s lands are less than three metres above sea level and a couple hundred metres wide, as explained by the Forced Migration Review (FMR).

With their feet already in the water, locals have witnessed sea levels rise by 5 to 11 centimetres in the past 30 years, according to NASA. This organisation estimates by 2050, an additional 15 to 30 centimetres will be observed. By the end of the century, it will approach 50 to 100 centimetres. Kiribati could, therefore, become the first country to disappear from the map due to climate change.

Image credit: A board sign standing on the highest peak of Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati. Photo by Miriam Moriati, provided to Greenauve.

As the waves creep further inland, the I-Kiribati people are losing the resources that sustain them. “The most pressing issue that inhabitants were talking about is water security”, explains Karoro.

Kiribati usually relies on two sources of water: rainwater and groundwater. However, “In a country with such a hot climate where rain hardly falls, everyone [now] depends on groundwater”, outlines Moriati.

With the rising sea level, groundwater is now being infiltrated by saltwater, contaminating the last reliable water source. “If there is too much water withdrawal and not enough recharge, [the water] gets brackish, saline”, explains Karoro.

In South Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati, “The government provides treated water to communities”, describes Karoro before adding, “But in the outer islands, they do not have this”.

“On top of it all, [sea level rise] degrades our soils, making it hard for us to plant healthy vegetables”, reveals Moriati. As stated by FMR, the quality of the soils in Kiribati is barren and limits the agricultural potential. “This has posed great health risks and malnutrition”, confides Moriati.

Loss of land is also a rising issue with coastal erosion. “Our coastlines have been greatly eroded, leaving our island thinner and thinner”, worries Moriati. According to the United Nations University for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), the sea level rise impacted 85% of households in South Tarawa between 2005 and 2015. Saltwater intrusions affected 49% of households in South Tarawa and 49% in outer islands. “The fear of sea level rise includes the fear of an inhabitable home”, shares Moriati.

But the I-Kiribati are even more worried about “[their] schools, clinics, or places that affect everybody”, explains Karoro. “The sense of community is very strong [in Kiribati]”, he adds.

Even if Kiribati’s future is uncertain, “People prefer to stay here”, affirms Karoro. Moriati declares, “I stand strongly by my belief that ‘we are home, nowhere else is home”. Supported by the government, the emphasis is placed on adaptation to protect the I-Kiribati people.

Image credit: Plantation of 2,000 mangroves on an impacted coastal area in Kiribati. Photo by Miriam Moriati, provided to Greenauve.

In 2024, the UN General Debate confirmed “that coastal protection remains a priority”. Nature-based solutions, such as planting mangroves, are “the safest and best way to protect our shoreline”, explains Karoro. As the Nature Conservancy states, mangroves defend the coastline “by reducing erosion and absorbing storm surge impacts”.

KiriCAN has been planting mangroves for many years, and “around these coming months, we plan… to plant around 3,000 mangroves in designated areas”, shares Karoro.

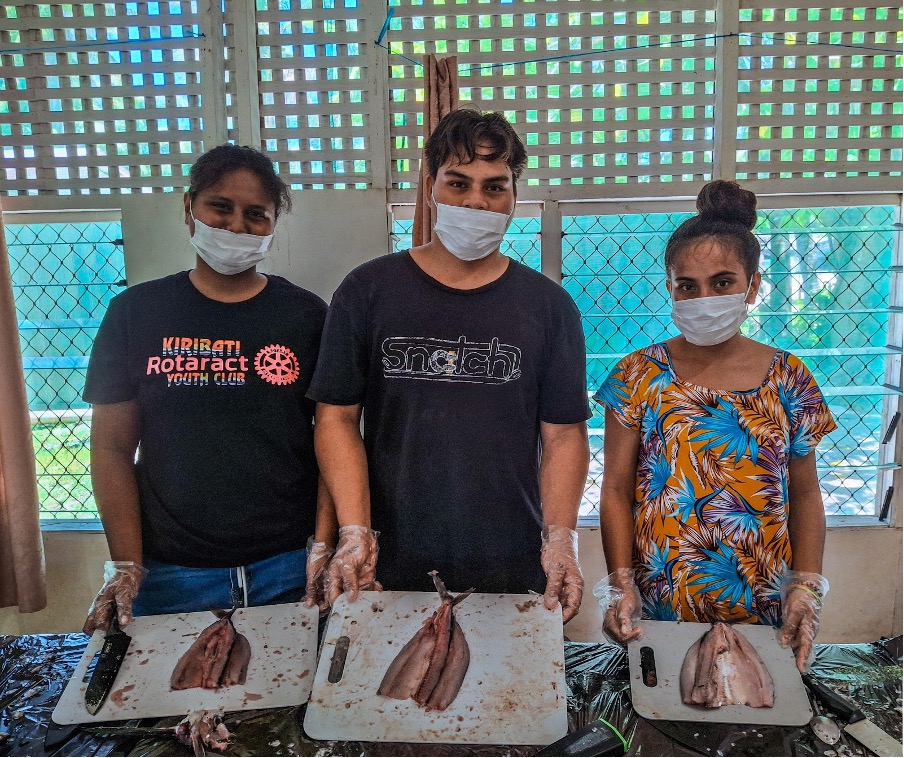

The I-Kiribati people also use their traditions to counter the effects of climate change. For example, Karoro shares that KiriCAN organised a workshop in March to teach youth how to preserve food “by using traditional methods”. Moreover, communities work together to build traditional sea walls called te buibui.

Image credit: Workshop to preserve food with traditional techniques (dried fish), organised by KiriCAN and Kiribati Rotaract Youth Club. Photo by Miriam Moriati, provided to Greenauve.

Adaptation is at the heart of preoccupations to mitigate climate change effects, but also to safeguard Kiribati’s history, culture and traditions. As Moriati sadly points out, “Our cultural way of life is slowly fading”.

The focus must be on education to ensure the survival of the I-Kiribati culture. According to Moriati, “There is a Kiribati saying ‘reireinna kai e uarereke‘ which translates to ‘teach them while they’re young”. She adds, “Children must be disciplined and taught their traditions and cultures”. “If Kiribati were to disappear, its history and culture must be safeguarded through the practice of language, dance, songs, food, and traditional survival skills. Practice sticks more than a mere display in a museum”, explains Moriati.

For Karoro, new technologies should be used to preserve the country’s culture. Taking the example of Tuvalu, a neighbouring Pacific nation that digitised their culture, Karoro explains, “There are some aspects of our traditions, cultures and practices… that we could digitise but not the land itself. When the land is gone, it’s gone”.

To prepare for this eventuality and relocate its people, the previous government purchased 5,461 acres of land in Fiji in 2014, according to Kiribati’s government. It is the first time a country has bought land for potential relocation.

Reports all point towards worsening the situation in the future, but Karoro affirms, “What we witness here is actually right here, outside.” The rise of the oceans is happening, and efforts to save Kiribati should be implemented by all, now.

Moriati concludes, “Climate change is not caused by Kiribati, nor by our neighbouring Pacific family. It is caused by… countries… blinded by their competitive race in developments and advancements.”

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment