Image credit: Photo by Alex Jones on Unsplash.

As spring arrives in the northern hemisphere, a large part of the population associates this with pollen allergies, also known as hay fever. These allergies affect about 40% of the population in Europe, according to a study published by Environmental Health Perspectives in 2017. Some countries are more impacted than others, such as England, where nearly 50% of the population is allergic to pollen.

Affecting already one in five people, reports are clear: “The rate [of pollen allergies] is expected to climb due to climate change”, announces Kira Hughes, graduate researcher specialised in airborne allergens at Deakin University, Australia.

When temperatures rise, seasons shift, and plants adapt by “starting to flower earlier and for longer”, according to Gesund Bund, the German health portal. As long as the conditions are favourable, plants will produce pollen.

Typically, pollen seasons start in March and last until autumn. But with climate change, they can appear as early as January.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) levels also influence pollen production. Plants feed on CO2 during a process called photosynthesis. An increased presence of CO2 causes plants to feed more and thus produce more pollen.

To support this theory, researchers have placed plants in growing chambers with different levels of CO2 to test pollen production. The results were striking.

The pollen production was twice as high in the chamber representing the CO2 levels in 1999 as the one representing the pre-industrial levels. The experiment went further and set up a chamber with the CO2 concentrations expected in 2060. The pollen production nearly doubled.

Image credit: Ragweed, also known as Ambrosia artemisiifolia, Donaubrunnfeld north of Manhartsbrunn, district Mistelbach, Lower Austria. Photo by Stefan Lefnaer, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In addition, climate change fosters the spread of invasive plants, such as ragweed (Ambrosia Artemisiifolia), by providing optimal conditions.

Ragweed is not only very invasive but also highly allergenic, explains the 2017 study, as every plant produces up to “1 billion grains a year”. In some areas of Europe, ragweed counts for 50% of pollen production.

The study affirms that the number of people affected by ragweed allergies will double in Europe, surging from 33 to 77 million by 2050. Dr Iain Lake, lead author of the study, said in a University of East Anglia (UEA) article, “Ragweed pollen allergy will become a common health problem across Europe, expanding into areas where it is currently uncommon”.

Ragweed can lead to increased local sensitisation, which is when people are becoming allergic due to exposure. The UEA explains, “You are more likely to become sensitised to an allergen the longer you are exposed to it”. It means everyone can become allergic overtime to ragweed or other plants.

Hay fever provokes symptoms, such as a runny nose or a cough, caused by inhaling pollen particles in the air. This is because the immune system perceives pollen as dangerous.

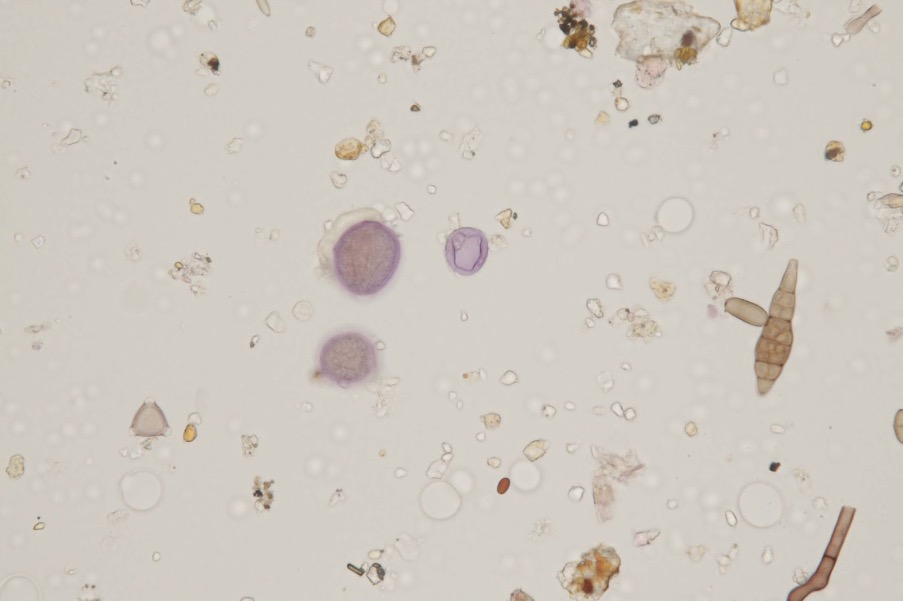

Image credit: Photo of pollen, fungal spores, and other airborne particles captured on microscope slide during a moderate-high pollen day in Melbourne, Australia. Photo by Kira Hughes, provided to Greenauve.

As the Gesund Bund emphasises, “The increase in pollen count can exacerbate existing allergies and prolong the acute symptom phases”. According to the predictions, managing symptoms will, therefore, become increasingly challenging. “Closing windows or reducing time outside can help, but they are not the perfect solutions because people do have to leave the house”, clarifies Hughes.

New solutions are being implemented, some radical, such as in Japan, where 40% of the population is allergic to pollen, with nearly 39% affected by cedar trees.

Cedar is a very allergenic tree planted in large quantities in Japan after the Second World War. To help manage the symptoms, the Japanese government decided in 2024 to cut 20% of the total cedar trees and replace them with low-pollen trees.

Additionally, the Canadian government is working to control ragweed, hoping it will reduce the pollen concentrations and exposure for those affected. However, Hughes insists, “Unless you’re making a giant net [to catch pollen in the air], I don’t think we’ll be able to control it”.

Indian scientists have suggested creating a pollen forecast similar to a weather app. Australia is already doing it, according to Hughes. She says it is an excellent idea because “the hardest thing as a hay fever sufferer is not knowing if the day is going to be bad or not”. Predicting daily pollen levels can help people with hay fever to manage their symptoms.

Hughes concludes, “The best solutions, especially on a global scale, are investing more in clean solutions, reducing the impact of climate change, and also looking more into better monitoring systems.”

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment