Image credit: Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia, February 2025 coral bleaching. Daniel Nicholson / Ocean Image Bank.

Since February 2025, the Ningaloo Reef has been struck by an “unprecedented” coral bleaching event due to a heatwave gripping Western Australia. Sea temperatures reached 4°C above seasonal norms in this area, according to the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

A survey has recently been conducted in Western Australia to understand the scale of this event. In some areas north of Ningaloo Reef, it revealed that up to 90 per cent corals have bleached – partially or completely.

For these scientists, the coral bleaching event in Ningaloo could be the worst observed in this reef.

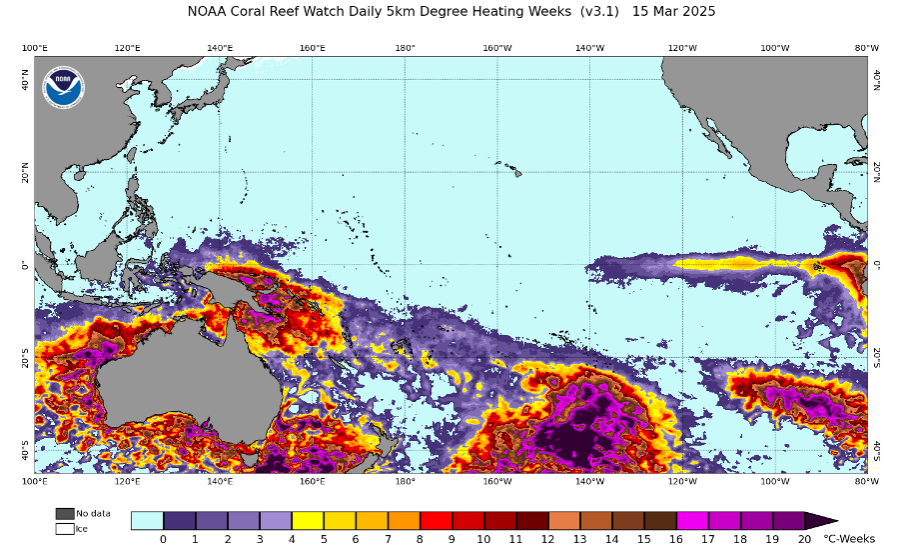

The event’s severity is measured by the “degree heating weeks” (DHW), a tool that tracks heat levels above normal over 12 weeks. NOAA explains when the level reaches 4 DHW, corals begin to bleach. At 8 DHW or higher, corals or the entire reef can die.

A level of 16 DHW was recorded at Ningaloo Reef this summer, the highest ever observed in the area. The WA director of Australian Marine Conservation Society, Paul Gamblin states, “Bleaching at Ningaloo is not normal… Large areas of coral could die in the weeks ahead. This is a red-alert moment”.

Image credit: NOAA Coral Reef Watch daily 5km degree heating weeks (DHW) (v3.1), 15th of March 2025.

Bleaching is a process by which the coral, facing stress, expels the microscopic algae that live on it, called zooxanthellae. As a mutualistic relationship, the coral protects the algae, which in return provide food to the coral.

The incredible colours of corals actually come from these algae. If they are expelled, only the white, fragile skeleton of the coral remains, which can lead to starvation and death.

Coral bleaching “does not always result in mortality”, explains Dr Tom Holmes, marine science program leader at the Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). But it greatly affects the survival of these organisms.

For corals to regenerate, they need time. However, with increasingly frequent heatwaves, corals’ survival can be jeopardised, especially as “sea surface temperatures will persist into May/June 2025”, affirms Dr Holmes.

Besides, the survey in Western Australia confirmed a rate of dead coral between 1 and 5 per cent. While this percentage seems relatively low, each coral supports thousands of species. With over 300 coral species in Ningaloo, even small amounts of death represent a real disaster.

This bleaching event further threatens Ningaloo Reef as the coral spawning (reproduction) happens in March and April for only a few days. “Corals reproduce by releasing their eggs and sperm all at the same time,” explains NOAA.

The overlap of bleaching and spawning periods could “reduce the reproductive potential” and births among corals, confirms Dr Holmes. “However, signs of reproduction were observed in unimpacted corals on the reef slope in late March,” he adds.

Coral reefs are crucial because, according to DBCA, they occupy “less than one per cent of the ocean floor, [and yet] support 25 per cent of all marine life”. Moreover, “Once these corals die, reefs rarely come back”, stresses WWF.

Dead corals would mean “thousands of marine species [could] lose critical habitats, as well as feeding and nesting grounds”, warns the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

Image credit: Coral Bay, Western Australia. Matt Curnock / Ocean Image Bank.

Ningaloo Reef welcomes more than 300 whale sharks annually, drawn by the coral spawning events. The reef is also home to more than 700 species of fish, 650 species of molluscs, nearly 600 species of crustaceans, more than 1,000 types of algae, and 155 species of sponges.

Spreading across 300 kilometres, Ningaloo Reef is considered the largest fringing reef in the world. It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2011 for its “incredible natural beauty” and for “containing the most important and significant natural habitats for in situ conservation of biological diversity”, according to DBCA.

Dr Holmes clarifies, “The full impacts of this heatwave will not be known for another 6-18 months”, before adding, “DBCA scientists and collaborators will continue to monitor Western Australia’s marine environment to assess the full extent and long-term impacts of this marine heatwave”.

“Members of the public can [also] report coral bleaching via the Australian Institute of Marine Science’s ArcGIS Collector app” to help assess this event, concludes Dr Holmes.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment