Image credit: Musca autumnalis. Photo by Ian Andrews.

Bird migration is a well-known phenomenon. However, less visible—but no less impressive—is the migration of a large number of insects within and across continents to feed and reproduce. Some insects even migrate hundreds or thousands of kilometres, silently traversing continents on wings that are barely visible to the human eye.

Among these winged migrants, an overlooked but vital group deserves more attention: the flies.

Studies on insect migration have “mainly focused on the larger, more charismatic insects” such as butterflies, dragonflies, and moths. But a new study published in March, Lords of the Flies: Dipteran Migrants Are Diverse, Abundant and Ecologically Important, highlights the importance of migratory flies.

About one million species of flies (Diptera) are estimated to exist globally, and 125,000 of them have been documented. These include familiar two-winged insects such as horseflies, crane flies, hoverflies, mosquitoes, and others.

The new study found that almost 600 of these species are likely to be migratory. Flies make up to 90% of insects in migratory assemblages at some global hotspots. As insect numbers are declining globally—at an estimated rate of 2% every year—the research underscores the ecological significance of these often-overlooked buzzing insects.

“No other order of insects seems to play as many ecological roles as the flies,” says Dr Will Hawkes from the Centre of Ecology and Conservation at Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall. About 60% of these migratory flies are involved in pollination, 35% in decomposition, and 10% in pest control.

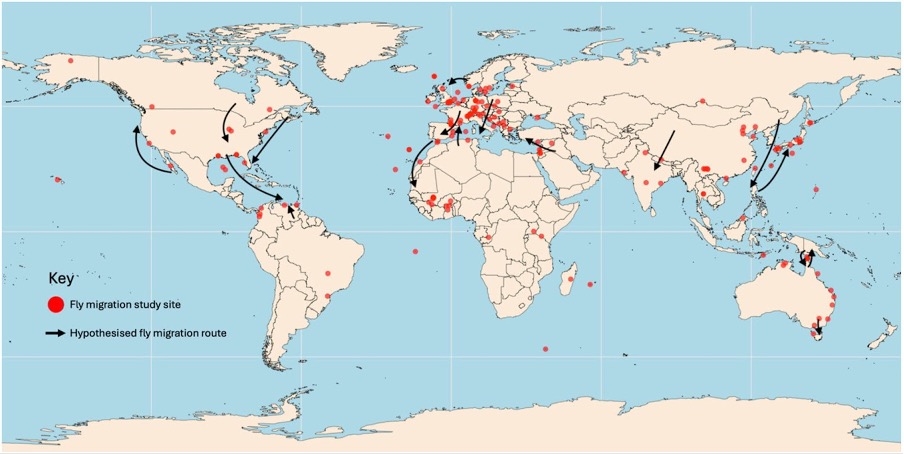

Image credit: Fly migration map. Photo by Dr. Will Leo Hawkes and team.

The study found that pollinating hoverflies alone visit 52% of major food crop plants globally—plants estimated to be worth around US$300 billion per year.

“Certainly, without flies, ecosystems and agriculture would be much poorer. As pollinators, they are more important than bees in some ways because they transport pollen (and the genetic material contained within) long distances between plant populations, allowing for gene flow,” Dr Hawkes explains. Without these flies, large-scale long-distance pollination would stop, leading to greater genetic inbreeding in plants.

They also help transfer nutrients, improving soil quality—an important function. In addition, some migratory flies are important controllers of agricultural pests such as aphids. The larvae of just two hoverfly species (marmalade and vagrant hoverflies) consume an estimated 10 trillion aphids each year in southern England alone, according to a press release. Without these flies, crop yields would drop dramatically.

Moreover, organic waste, such as dung or animal carcasses, would litter the land as some migratory flies are vital decomposers. Common drone flies play an important role in decomposition. For instance, the study notes that the larvae from just 8,800 eggs of the common drone fly can decompose up to 100 kg of pig slurry, transforming it into organic compost.

Some highly mobile species may also connect distant habitats by moving genetic material, such as pollen, back and forth—boosting plant genetic diversity.

“Flies are probably the most numerous of migrants, so the impact of the roles they play is bigger than any other migratory group,” Dr Hawkes says.

Image credit: Pied Hoverfly. Photo by Ian Andrews.

Despite their crucial ecological roles, migratory flies are increasingly at risk due to rapid urbanisation, intensive farming, and the widespread destruction of wetlands—factors that have rendered vast areas inhospitable and disrupted their migration routes, researchers warn.

“Many species that benefit humans are now under serious threat from climate change and human activity, and some may vanish before we even get a chance to study them,” says Dr Hawkes. “It’s no exaggeration to say that without migratory flies, both human societies and ecosystems would face immense challenges.”

Conservation efforts, he emphasises, must go beyond isolated habitat protection. “To truly safeguard these insects, their entire migratory pathways need to be viable and connected.”

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a comment